Art, Life and Vision in London

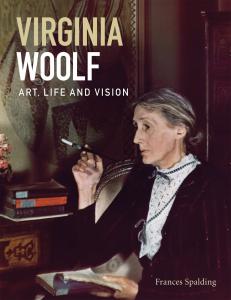

The Virginia Woolf Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery took place between 10 July and 26 October 2014, and covered the writer’s life from her early childhood to her death. The photos, hand-written diary entries and letters, as well as extracts from Woolf’s writings, the first editions of her books and the art works of her sister, Vanessa Bell, and of friends were on loan from museums and libraries all over the world. The greatest strength of this outstanding exhibition was that it concentrated not only on the well-known events of the writer’s private and public life, but it also offered insight into the historical backgrounds of the time in which Woolf lived. Frances Spalding, the guest curator of the exhibition, also published a book based on the whole material of the collection, with the title Virginia Woolf – Art, Life and Vision. This joint enterprise is unique though, because Spalding took great pains to introduce several lesser-known, but all the more defining facts which had greatly influenced Woolf. It may be worth highlighting some of them, as they appeared in the gallery rooms.

Although the exhibition followed the writer’s life more or less in a chronological order, at the entrance, next to Woolf’s professional portrait from 1927, the visitors found themselves face to face with a photo of the demolished walls of 52 Tavistock Square, where the Woolfs had lived till 1939. The choice of the curator may have fallen to this image, right at the beginning of the collection, because the Second World War, the bombings of London, and the destruction of their one-time home – their actual flat had been damaged as well – might have been crucial factors which had led to Woolf’s last bout of depression and her eventual suicide in 1941. This powerful image offered a striking contrast with the childhood photos and stories on the opposite wall of the room. One of the curiosities of this first section was a manuscript of the family journal, Hyde Park Gate News, mostly written by the young Virginia Stephen, an eloquent testimony of her writing brilliance at the age of 10. To illustrate the Stephens’ distinguished status in the late Victorian society, next to the family snapshots the photos of Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson and Charles Darwin were displayed as acquaintances of Woolf’s father, Leslie Stephen.

The segments which comprised the Stephen sisters and their two brothers’ new and liberated life and the beginning of their career would not have been complete without the photos and painted portraits of all their friends with whom together they became known as the Bloomsbury Set. Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Lytton and James Strachey, Leonard Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, and Sidney Saxon Turner all participated in leaving the Victorian traditions behind. The friends’ relationship to and influence on each other was represented in diverse ways. Lytton Strachey’s letter to his brother, James, in which he announces that he proposed to Virginia but the next day he withdrew the offer, was an interesting item in one of the glass cases. Vanessa Bell’s faceless painted portraits which are said to have inspired Woolf’s way of depersonalisation in her experimental novels stood for the sisters’ search for a new means of portrayal. This section presented the Woolfs’ small printing enterprise, the later influential Hogarth Press, which produced their own works as well, mostly with the cover designs of Vanessa Bell. T. S. Eliot’s poems from 1919, his Waste Land from 1923, and the Hogarth’s second publication, Katherine Mansfield’s Prelude were also among the displayed items owing to their extreme importance in the first steps of the Woolf’s successful undertaking. Woolf’s relationship with Mansfield was rhapsodic but inspiring for both of them, which the curator indicated with letters between the two of them.

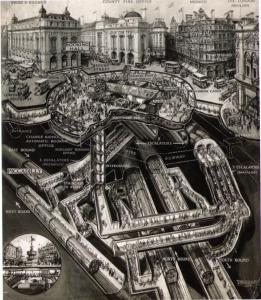

The section which gave place to Woolf’s most productive years elaborated not only on her novels from Mrs Dalloway to Flush but also on factors and people who served as stimulation for the writer. Photos of and a letter to Vita Sackville-West deserved central places in this room for the crucial role of the two authors’ relationship in Woolf’s most successful years. The extension of the London Underground aroused ambivalence in Woolf although she was well aware of its vital importance in the infrastructure of a modern city. For this reason she referred to it in many of her writings. The displayed drawing of Douglas MacPherson on the tube connections under Piccadilly Circus could have been the source of a soliloquy in the author’s novel The Waves which is considered as her greatest achievement in her quest of her own voice.

The final section, comprising the years between 1933 and 1941, contained such materials as Picasso’s Weeping Woman, a drawing which he had donated to the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief and a poster which announced the painter’s London exhibition for the same cause. Among the patrons of the exhibition we can see Woolf’s name as well. The Spanish civil war changed the Bell family and Virginia Woolf’s life for ever, as her nephew, Julian, lost his life as an ambulance driver for the Spanish Medical Aid. The Gestapo’s Black Book or Special Search List from World War II was that document which caused the Woolfs’ plotting their suicide. This 144-page book with the names of 2820 prominent people to be arrested in case of a Nazi invasion of Britain, including Churchill and Bertrand Russell for example, lay in one of the cases opened at the Woolfs. The well known two suicide notes written to Leonard Woolf and Vanessa Bell were among the last items displayed, as well as Woolf’s walking stick with which she walked to the River Ouse to her death.

Wonderfully fitted to the constraints of museum walls and cases, this exhibition offered a visual biography, a complex portrait of Virginia Woolf and the aspects that contributed to her multi-sided work. This highly educating, wide-ranging archive material which introduced most of the events and people whose influence shaped Woolf’s private and professional life at the heart of modernism, definitely got visitors closer to one of the most famous writers of the 20th century. After witnessing the huge mass of people laboriously examining the items, even in the last days of the show, it seems not too far-fetched to say that this collection begs to be taken on a global tour. If this will not happen, Spalding’s wonderful book may compensate all who missed the exhibition.

Virginia Woolf – Art, Life and Vision

National Portrait Gallery, London

10 July – 26 October 2014

Frances Spalding

Facebook-hozzászólások