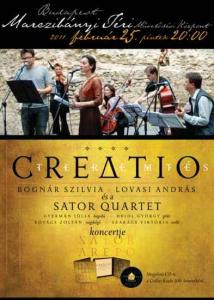

'Contemporary Sacral Music'

Prayer, poetry, song? Medieval latin hymns belong to all three genres. Now, they rose for one night, performed by the Sator Quartet featuring Szilvia Bognár and András Lovasi.

You shouldn't be ashamed if you haven't heard the ensemble's name before. Sator (Latin for sower, planter, begetter, father, creator) Quartet wasn't formed long ago. However, their fame got round quickly by word of mouth. There is a paricularly strong following in Pécs as a result of the majority of members coming from the Southern Hungarian city. However, what really makes them special is the blend of four different musical languages. Early medieval aesthetics researcher and head of department at the University of Pécs, guitarist György Heidl seems to be the spiritus rector of the group. Originally, he put János Lackfi's poems to music which became known, what's more, famous with the singing of András Lovasi in his Hangzó Helikon series. His next idea was even more daring: he composed contemporary (not rock) music to medieval hymns.

Available on CD, the music pushes the envelope, mainly because the songwriter allows the musicians' considerably different backgrounds to show. Júlia Gyermán of Danubia orchestra is a classical violinist who also plays with Csaba Vedres in Kariosz quartet. Viktória Szakács plays the cello in the Salzburger Kammerorchester besides being section leader in the Pannon Philharmonic Orchestra. Upright bassist Zoltán Kovács is familiar with both popular music and jazz as well as having a feeling for folk music. No wonder it isn't easy to define Sator Quartet. Probably the most fitting category came from András Lovasi who calls it 'contemporary sacral music'. The two singers also come from fairly different musical backgrounds. Their task is to adapt the Latin lyrics to the newly composed melodies that totally break away from the traditional musical forms of psalms. They do all this without forgetting where they come from, that is the world of folk music for Szilvia Bognár and the popular rock scene for Lovasi.

And here we are together at Marczibányi tér on the last Sunday night of the winter, in a partly refurbished old community centre and a fairly big audience. The orchestra enters the stage with Szilvia Bognár and we listen to a Csango kyrie, crystal clear, performed bravely and crisply. It soon becomes clear that the sacrality of the music isn't just an attraction or an umbrella, but a mindset, a clever devotion.

Then, the show takes off. Deus Creator Omnium, the hymn of Saint Ambrose is first, followed by prayers for every day of the week, that cover the Book of Genesis from the praying individual's aspect. They raise questions concerning life and death; regret and forgiveness both have a place in these texts. "The wounds of the burnt soul / are dewed by your grace, / so his sins be washed away by tears, / and deceit be ended." Some parts are sung in Hungarian but the language of the majority of the songs is Latin. It is neither sweet nor easy and joyful; it is very far from the atmosphere of a guitar mass. In certain parts even the ears' need for harmony stays unfulfilled. The performance is characterised by brave harmonic and rhythmic breaks; the guitarrist's fingers are racing up and down the strings, the bows are flying. The music is all-feeling, all-thought without satisfying the demand for cheesiness. Still, when the dynamic fades, the singing becomes a confession or exactly the opposite; carlessly, it flies high and takes you with it. This is when the heart can't resist and your eyes start watering.

The music has its flaws. As a composer, Heidl still seems to explore his own boundaries, which at some points, results in disharmony between the pure sentiments and the musical implementation. Also as a guitarist, he seems to run after the strings but even his clumsiness shows virtuosity; his mistakes are dominated by the stillness of the soul. Lovasi also has some difficulties finding the right pitch making him fall or rise to Szilvia Bognár's voice. But this is what hymns are all about after all. This is how a sinner is searching for the clear tone in their prayer, counscious of the certain passing. "Our souls shall not be drowned by sins, / and lose their lives, / for it does not forever mind, / bound by the shackles of sin." This is how music, lyrics and performance revolve around each other; it is a dance of three men and three women around the unspeakable. The body can't always keep up with the rhythm. The soul is faster and needs more than what the mortal shell can offer – but real music is not perfect; it is its frailty and spontaneity that moves you. For instance how the cellist struggles during the encore (that is the would-be hit Caeli Deus Sanctissime) with her detuned instrument (and perhaps a broken string even?) and gives up realising it won't work, then just sits smiling, not playing, only listening and taking in the heavenly message. Then, she stands up and bows together with the other members.

Facebook-hozzászólások