Primeval Time, Primeval Book, Primeval Cosmos

When Kazimierz Brandys finished his novel Rondo in the late seventies, he wrote in his diary that it had been the last occasion he toiled with fiction and the conventions of a major novel and that he wouldn't build any more illusion machines, because he could express himself without those. He kept his word (or fulfilled his threat?); during the last two decades of his life, he entertained, then bored his less and less accessible readers with diaries, biographical essays and describing the hardships of himself and his elaborately chosen mirroring selves. The Polish spent the haunting decade of the Jaruzelski era reading diaries, memoirs, reports and documentaries.

However, by the time they understood all of it, everything had changed. When the foreign regime ends in Poland, people immediately reevaluate literature. They happily get rid of century-long obsessions as if they wouldn't understand how they could force the ascetic ideology of messianism unto themselves. This is what happened in 1918 and 1990. Twenty years ago, everybody looked at the new names, expecting the miracle, the free Polish literature of peaceful times that restores the joy of reading. The publishers became a part of the market and rejoined the authors with the readers, handing fiction its original rights.

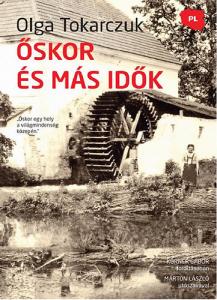

This hopeful decade saw the beginning of Olga Tokarchuk's career as a novelist. Her background absolutely fit the ideals of new writers: qualified in psychology, a storyteller with Jungian ideas, she didn't present the public side of the personality, instead she dove into the deepest reaches that touch myths. It's as if she brought the good news to the reader that they don't have to cope with the demons of Polish history anymore, and what they need the most from now on is self-recognition. Her first two novels, The Journey of the Book-People (original title: Podróż ludzi księgi) and E. E. weren't the real thing but Primeval and Other Times (Prawiek i inne czasy) was such a big hit that it counquered theatres and even secondary schools where it got onto the obligatory reading lists. This is when Olga Tokarczuk's fate was sealed: she's a novelist maybe one of the most succesful of this era, whose works are translated in many countries from Brazil to China and are read everywhere from New Zealand to the campus in Piliscsaba, all without having to turn into Coelho.

Primeval and Other Times is a well-founded novel. It's got underground halls as big as those in the Wieliczka Salt Mine. The psychological novel spanning across several decades has mythographical dimensions, and naturalistic descriptions get on really well with symbolic thoughts. There are everyday people and mythological figures (eg. unable to fit into the country culture, Kłoska matches the Greek goddess Demeter), but Tokarczuk manages to portray the insides of even the Virgin Mary sculpture in the church, as well as animals, trees and objects. History also plays a significant role in the story, since the village doesn't miss either world war. However, this isn't the primary theme; it is the timeless matriarchal culture, constantly reviving through fertility rites.

Although the village situated at the centre of the universe, guarded by four archangels, surrounded by an invisible wall (so that no one can leave – those that set forth fall asleep at the borders of the village and only dream that they are someplace else) is called Primeval, it also recalls prehistoric times. The Polish didn't fully break away from the pre-Christian 'barbarian Europe', the rich culture of the settled peoples founded on cousinly and neighbourly relations (the book also presents the Slavic god watching the four corners of the world with its four faces), but literature can dig this deep only in rare cases. Just like antother obligatory reading, Forefathers' Eve (Dziady), describing the togetherness of the living and the dead.

Olga Tokarczuk, Őskor és más idők, translated by Gábor Körner, L'Harmattan, Budapest, 2011.

Facebook-hozzászólások